IELTS Online

IELTS Reading Cambridge 16 test 4: Dịch và giải chi tiết đáp án

Mục lục [Ẩn]

Bạn đang luyện IELTS Reading với Cambridge 16 Reading Test 4 nhưng chưa chắc cách chọn đáp án và vì sao đúng/sai. Bài viết này sẽ dịch sát nghĩa từng đoạn, kèm giải chi tiết đáp án từng câu (vì sao đúng – vì sao sai), giúp bạn học được cách định vị keyword, nhận diện bẫy và tối ưu thời gian làm bài để cải thiện band nhanh hơn.

1. Đáp án IELTS Reading Cambridge 16 test 4

Dưới đây là đáp án chi tiết IELTS Reading Cambridge 16 test 4:

|

11. gold |

21. B |

31. vii |

|

12. (the) architect |

22. C |

32. v |

|

13. (the) harbor |

23. YES |

33. C |

|

14. A |

24. NO |

34. B |

|

15. B |

26. NOT GIVEN |

35. A |

|

16. D |

26. YES |

36. YES |

|

17. B |

27. iii |

37. NOT GIVEN |

|

18. D |

28. vi |

38. YES |

|

19. H |

29. ii |

39. NO |

|

20. F |

30. i |

40. YES |

>> Xem thêm: Giải đề IELTS Reading Cam 16, Test 2: I Contain Multitudes

2. Cambridge 16 test 4 passage 1: Roman tunnels

READING PASSAGE 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13 which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

Roman tunnels

The Romans, who once controlled areas of Europe, North Africa and Asia Minor, adopted the construction techniques of other civilizations to build tunnels in their territories

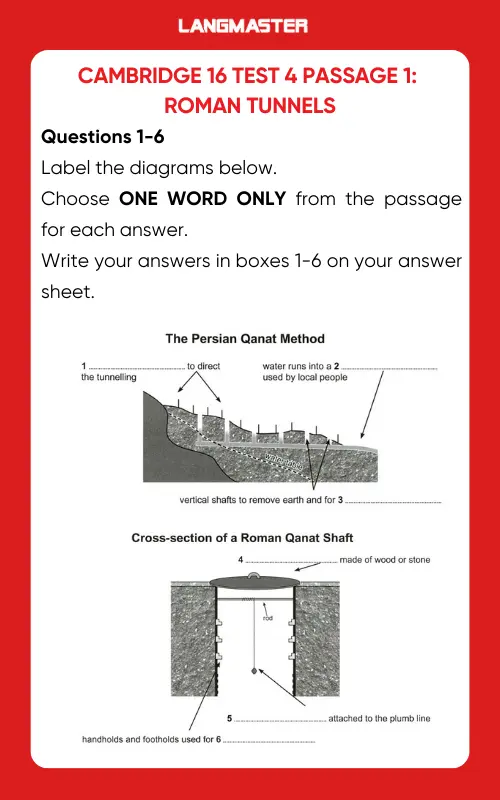

The Persians, who lived in present-day Iran, were one of the first civilizations to build tunnels that provided a reliable supply of water to human settlements in dry areas. In the early first millennium BCE, they introduced the qanat method of tunnel construction, which consisted of placing posts over a hill in a straight line, to ensure that the tunnel kept to its route, and then digging vertical shafts down into the ground at regular intervals. Underground, workers removed the earth from between the ends of the shafts, creating a tunnel. The excavated soil was taken up to the surface using the shafts, which also provided ventilation during the work. Once the tunnel was completed, it allowed water to flow from the top of a hillside down towards a canal, which supplied water for human use. Remarkably, some qanats built by the Persians 2,700 years ago are still in use today.

They later passed on their knowledge to the Romans, who also used the qanat method to construct water-supply tunnels for agriculture. Roma qanat tunnels were constructed with vertical shafts dug at intervals of between 30 and 60 meters. The shafts were equipped with handholds and footholds to help those climbing in and out of them and were covered with a wooden or stone lid. To ensure that the shafts were vertical, Romans hung a plumb line from a rod placed across the top of each shaft and made sure that the weight at the end of it hung in the center of the shaft. Plumb lines were also used to measure the depth of the shaft and to determine the slope of the tunnel. The 5.6-kilometer-long Claudius tunnel, built in 41 CE to drain the Fucine Lake in central Italy, had shafts that were up to 122 meters deep, took 11 years to build and involved approximately 30,000 workers.

By the 6th century BCE, a second method of tunnel construction appeared called the counter-excavation method, in which the tunnel was constructed from both ends. It was used to cut through high mountains when the qanat method was not a practical alternative. This method required greater planning and advanced knowledge of surveying, mathematics and geometry as both ends of a tunnel had to meet correctly at the center of the mountain. Adjustments to the direction of the tunnel also had to be made whenever builders encountered geological problems or when it deviated from its set path. They constantly checked the tunnel’s advancing direction, for example, by looking back at the light that penetrated through the tunnel mouth, and made corrections whenever necessary. Large deviations could happen, and they could result in one end of the tunnel not being usable. An inscription written on the side of a 428-meter tunnel, built by the Romans as part of the Saldae aqueduct system in modern-day Algeria, describes how the two teams of builders missed each other in the mountain and how the later construction of a lateral link between both corridors corrected the initial error.

The Romans dug tunnels for their roads using the counter-excavation method, whenever they encountered obstacles such as hills or mountains that were too high for roads to pass over. An example is the 37-meter-long, 6-meter-high, Furlo Pass Tunnel built in Italy in 69-79 CE. Remarkably, a modern road still uses this tunnel today. Tunnels were also built for mineral extraction. Miners would locate a mineral vein and then pursue it with shafts and tunnels underground. Traces of such tunnels used to mine gold can still be found at the Dolaucothi mines in Wales. When the sole purpose of a tunnel was mineral extraction, construction required less planning, as the tunnel route was determined by the mineral vein.

Roman tunnel projects were carefully planned and carried out. The length of time it took to construct a tunnel depended on the method being used and the type of rock being excavated. The qanat construction method was usually faster than the counter-excavation method as it was more straightforward. This was because the mountain could be excavated not only from the tunnel mouths but also from shafts. The type of rock could also influence construction times. When the rock was hard, the Romans employed a technique called fire quenching which consisted of heating the rock with fire, and then suddenly cooling it with cold water so that it would crack. Progress through hard rock could be very slow, and it was not uncommon for tunnels to take years, if not decades, to be built. Construction marks left on a Roman tunnel in Bologna show that the rate of advance through solid rock was 30 centimeters per day. In contrast, the rate of advance of the Claudius tunnel can be calculated at 1.4 meters per day. Most tunnels had inscriptions showing the names of patrons who ordered construction and sometimes the name of the architect. For example, the 1.4-kilometer Çevlik tunnel in Turkey, built to divert the floodwater threatening the harbor of the ancient city of Seleuceia Pieria, had inscriptions on the entrance, still visible today, that also indicate that the tunnel was started in 69 CE and was completed in 81 CE.

Questions 1-6

Label the diagrams below.

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 1-6 on your answer sheet.

Questions 7-10

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1?

In boxes 7-10 on your answer sheet, write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

-

7 The counter-excavation method completely replaced the qanat method in the 6th century BCE.

-

8 Only experienced builders were employed to construct a tunnel using the counter-excavation method.

-

9 The information about a problem that occurred during the construction of the Saldae aqueduct system was found in an ancient book.

-

10 The mistake made by the builders of the Saldae aqueduct system was that the two parts of the tunnel failed to meet.

Questions 11-13

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 11-13 on your answer sheet.

-

11 What type of mineral were the Dolaucothi mines in Wales built to extract?

-

12 In addition to the patron, whose name might be carved onto a tunnel?

-

13 What part of Seleuceia Pieria was the Çevlik tunnel built to protect?

Trên đây là toàn bộ đề thi Cambridge 16 test 4 passage 1: Roman tunnels, bạn có thể tham khảo bài dịch và giải thích đáp án chi tiết TẠI ĐÂY.

3. Cambridge 16 test 4 passage 2: Changes in reading habits

READING PASSAGE 2

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-26 which are based on Reading Passage 2 below.

Changes in reading habits

What are the implications of the way we read today?

Look around on your next plane trip. The iPad is the new pacifier for babies and toddlers. Younger school-aged children read stories on smartphones; older kids don’t read at all, but hunch over video games. Parents and other passengers read on tablets or skim a flotilla of email and news feeds. Unbeknown to most of us, an invisible, game-changing transformation links everyone in this picture: the neuronal circuit that underlies the brain’s ability to read is subtly, rapidly changing and this has implications for everyone from the pre-reading toddler to the expert adult.

As work in neurosciences indicates, the acquisition of literacy necessitated a new circuit in our species’ brain more than 6,000 years ago. That circuit evolved from a very simple mechanism for decoding basic information, like the number of goats in one’s herd, to the present, highly elaborated reading brain. My research depicts how the present reading brain enables the development of some of our most important intellectual and affective processes: internalized knowledge, analogical reasoning, and inference; perspective-taking and empathy; critical analysis and the generation of insight. Research surfacing in many parts of the world now cautions that each of these essential ‘deep reading’ processes may be under threat as we move into digital-based modes of reading.

This is not a simple, binary issue of print versus digital reading and technological innovations. As MIT scholar Sherry Turkle has written, we do not err as a society when we innovate but when we ignore what we disrupt or diminish while innovating. In this hinge moment between print and digital cultures, society needs to confront what is diminishing in the expert reading circuit, what our children and older students are not developing, and what we can do about it.

We know from research that the reading circuit is not given to human beings through a genetic blueprint like vision or language; it needs an environment to develop. Further, it will adapt to that environment’s requirements – from different writing systems to the characteristics of whatever medium is used. If the dominant medium advantages processes that are fast, multi-task oriented and well-suited for large volumes of information, like the current digital medium, so will the reading circuit. As UCLA psychologist Patricia Greenfield writes, the result is that less attention and time will be allocated to slower, time-demanding deep reading processes.

Increasing reports from educators and from researchers in psychology and the humanities bear this out. English literature scholar and teacher Mark Edmundson describes how many college students actively avoid the classic literature of the 19th and 20th centuries in favour of something simpler as they no longer have the patience to read longer, denser, more difficult texts. We should be less concerned with students’ ‘cognitive impatience’, however, than by what may underlie it: the potential inability of large numbers of students to read with a level of critical analysis sufficient to comprehend the complexity of thought and argument found in more demanding texts.

Multiple studies show that digital screen use may be causing a variety of troubling downstream effects on reading comprehension in older high school and college students. In Stavanger, Norway, psychologist Anne Mangen and colleagues studied how high school students comprehend the same material in different mediums. Mangen’s group asked subjects questions about a short story whose plot had universal student appeal; half of the students read the story on a tablet, the other half in paperback. Results indicated that students who read on print were superior in their comprehension to screen-reading peers, particularly in their ability to sequence detail and reconstruct the plot in chronological order.

Ziming Liu from San Jose State University has conducted a series of studies which indicate that the ‘new norm’ in reading is skimming, involving word-spotting and browsing through the text. Many readers now use a pattern when reading in which they sample the first line and then word-spot through the rest of the text. When the reading brain skims like this, it reduces time allocated to deep reading processes. In other words, we don’t have time to grasp complexity, to understand another’s feelings, to perceive beauty, and to create thoughts of the reader’s own.

The possibility that critical analysis, empathy and other deep reading processes could become the unintended ‘collateral damage’ of our digital culture is not a straightforward binary issue about print versus digital reading. It is about how we all have begun to read o various mediums and how that changes not only what we read, but also the purposes for which we read. Nor is it only about the young. The subtle atrophy of critical analysis and empathy affects us all equally. It affects our ability to navigate a constant bombardment of information. It incentivizes a retreat to the most familiar stores of unchecked information, which require and receive no analysis, leaving us susceptible to false information and irrational ideas.

There’s an old rule in neuroscience that does not alter with age: use it or lose it. It is a very hopeful principle when applied to critical thought in the reading brain because it implies choice. The story of the changing reading brain is hardly finished. We possess both the science and the technology to identify and redress the changes in how we read before they become entrenched. If we work to understand exactly what we will lose, alongside the extraordinary new capacities that the digital world has brought us, there is as much reason for excitement as caution.

Questions 14-17

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 14-17 on your answer sheet.

14 What is the writer’s main point in the first paragraph?

- Our use of technology is having a hidden effect on us.

- Technology can be used to help youngsters to read.

- Travellers should be encouraged to use technology on planes.

- Playing games is a more popular use of technology than reading.Shop for bestsellers

15 What main point does Sherry Turkle make about innovation?

- Technological innovation has led to a reduction in print reading.

- We should pay attention to what might be lost when innovation occurs.

- We should encourage more young people to become involved in innovation.

- There is a difference between developing products and developing ideas.

16 What point is the writer making in the fourth paragraph?

- Humans have an inborn ability to read and write.

- Reading can be done using many different mediums.

- Writing systems make unexpected demands on the brain.

- Some brain circuits adjust to whatever is required of them.

17 According to Mark Edmundson, the attitude of college students

- has changed the way he teaches.

- has influenced what they select to read.

- does not worry him as much as it does others.

- does not match the views of the general public.

Questions 18-22

Complete the summary using the list of words, A-H, below.

Write the correct letter, A-H, in boxes 18-22 on your answer sheet.

Studies on digital screen use

There have been many studies on digital screen use, showing some 18 ………………… trends. Psychologist Anne Mangen gave high-school students a short story to read, half using digital and half using print mediums. Her team then used a question-and-answer technique to find out how 19 ………………… each group’s understanding of the plot was. The findings showed a clear pattern in the responses, with those who read screens finding the order of information 20 ………………… to recall.

Studies by Ziming Liu show that students are tending to read 21 ………………… words and phrases in a text to save time. This approach, she says, gives the reader a superficial understanding of the 22 ………………… content of material, leaving no time for thought.

- fast

- isolated

- emotional

- worrying

- many

- hard

- combined

- thorough

Questions 23-26

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in Reading Passage 2?

In boxes 23-26 on your answer sheet, write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

FALSE if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

23 The medium we use to read can affect our choice of reading content.

24 Some age groups are more likely to lose their complex reading skills than others.

25 False information has become more widespread in today’s digital era.

26 We still have opportunities to rectify the problems that technology is presenting.

Trên đây là toàn bộ đề thi Cambridge 16 test 4 passage 2: Changes in reading habits, bạn có thể tham khảo bài dịch và giải thích đáp án chi tiết TẠI ĐÂY.

>> Xem thêm:

4. Cambridge 16 test 4 passage 3: Attitudes towards Artificial Intelligence

4.1. Đề thi Cambridge 16 test 4 passage 3

READING PASSAGE 3

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27-40 which are based on Reading Passage 3 below.

Attitudes towards Artificial Intelligence

A. Artificial intelligence (AI) can already predict the future. Police forces are using it to map when and where crime is likely to occur. Doctors can use it to predict when a patient is most likely to have a heart attack or stroke. Researchers are even trying to give AI imagination so it can plan for unexpected consequences.

Many decisions in our lives require a good forecast, and AI is almost always better at forecasting than we are. Yet for all these technological advances, we still seem to deeply lack confidence in AI predictions. Recent cases show that people don’t like relying on AI and prefer to trust human experts, even if these experts are wrong.

If we want AI to really benefit people, we need to find a way to get people to trust it. To do that, we need to understand why people are so reluctant to trust AI in the first place.

(Trí tuệ nhân tạo (AI) giờ đây đã có thể dự đoán tương lai. Lực lượng cảnh sát đang dùng AI để lập bản đồ thời gian và địa điểm mà tội phạm có khả năng xảy ra. Bác sĩ có thể dùng AI để dự đoán khi nào một bệnh nhân có nguy cơ cao bị đau tim hoặc đột quỵ. Các nhà nghiên cứu thậm chí còn đang cố gắng “trao cho AI trí tưởng tượng” để nó có thể lập kế hoạch cho những hậu quả bất ngờ.

Nhiều quyết định trong cuộc sống của chúng ta đòi hỏi một dự báo tốt, và AI gần như luôn dự báo tốt hơn con người. Thế nhưng, dù công nghệ đã tiến bộ như vậy, chúng ta dường như vẫn thiếu niềm tin sâu sắc vào các dự đoán của AI. Nhiều trường hợp gần đây cho thấy mọi người không thích dựa vào AI và предпоч́ chọn tin vào chuyên gia con người, ngay cả khi những chuyên gia đó sai.

Nếu muốn AI thực sự mang lại lợi ích cho con người, chúng ta cần tìm cách khiến mọi người tin tưởng nó. Và để làm được điều đó, trước hết cần hiểu vì sao ngay từ đầu con người lại miễn cưỡng tin AI đến vậy.)

B. Take the case of Watson for Oncology, one of technology giant IBM’s supercomputer programs. Their attempt to promote this program to cancer doctors was a PR disaster. The AI promised to deliver top-quality recommendations on the treatment of 12 cancers that accounted for 80% of the world’s cases. But when doctors first interacted with Watson, they found themselves in a rather difficult situation. On the one hand, if Watson provided guidance about a treatment that coincided with their own opinions, physicians did not see much point in Watson’s recommendations. The supercomputer was simply telling them what they already knew, and these recommendations did not change the actual treatment.

On the other hand, if Watson generated a recommendation that contradicted the experts’ opinion, doctors would typically conclude that Watson wasn’t competent. And the machine wouldn’t be able to explain why its treatment was plausible because its machine-learning algorithms were simply too complex to be fully understood by humans. Consequently, this has caused even more suspicion and disbelief, leading many doctors to ignore the seemingly outlandish AI recommendations and stick to their own expertise.

(Hãy lấy trường hợp Watson for Oncology, một trong những chương trình siêu máy tính của “ông lớn” công nghệ IBM. Nỗ lực quảng bá chương trình này tới các bác sĩ ung thư đã trở thành một thảm họa truyền thông. AI này hứa hẹn đưa ra các khuyến nghị điều trị chất lượng cao cho mười hai loại ung thư chiếm tám mươi phần trăm số ca trên toàn thế giới. Nhưng khi các bác sĩ lần đầu tương tác với Watson, họ rơi vào một tình thế khá khó xử. Một mặt, nếu Watson đưa ra hướng dẫn điều trị trùng với quan điểm của họ, các bác sĩ không thấy khuyến nghị của Watson có nhiều ý nghĩa. Siêu máy tính chỉ đơn giản nói lại điều họ vốn đã biết, và những khuyến nghị đó không làm thay đổi cách điều trị thực tế.

Mặt khác, nếu Watson tạo ra một khuyến nghị trái với ý kiến của các chuyên gia, bác sĩ thường kết luận rằng Watson không đủ năng lực. Và cỗ máy cũng không thể giải thích vì sao phương án điều trị của nó hợp lý, bởi các thuật toán học máy của nó quá phức tạp để con người có thể hiểu đầy đủ. Hệ quả là điều này càng làm tăng sự nghi ngờ và hoài nghi, khiến nhiều bác sĩ phớt lờ những khuyến nghị AI nghe có vẻ “khó tin” và bám vào chuyên môn của chính mình.)

C. This is just one example of people’s lack of confidence in AI and their reluctance to accept what AI has to offer. Trust in other people is often based on our understanding of how others think and having experience of their reliability. This helps create a psychological feeling of safety. AI, on the other hand, is still fairly new and unfamiliar to most people. Even if it can be technically explained (and that’s not always the case), AI’s decision-making process is usually too difficult for most people to comprehend. And interacting with something we don’t understand can cause anxiety and give us a sense that we’re losing control.

Many people are also simply not familiar with many instances of AI actually working, because it often happens in the background. Instead, they are acutely aware of instances where AI goes wrong. Embarrassing AI failures receive a disproportionate amount of media attention, emphasising the message that we cannot rely on technology. Machine learning is not foolproof, in part because the humans who design it aren’t.

(Đây chỉ là một ví dụ về việc con người thiếu tự tin vào AI và ngần ngại chấp nhận những gì AI mang lại. Niềm tin vào người khác thường dựa trên việc ta hiểu họ suy nghĩ như thế nào và có kinh nghiệm về độ đáng tin cậy của họ. Điều đó tạo ra một cảm giác an toàn về mặt tâm lý. Ngược lại, AI vẫn còn khá mới mẻ và xa lạ với đa số mọi người. Ngay cả khi có thể giải thích về mặt kỹ thuật (mà điều này không phải lúc nào cũng làm được), quá trình ra quyết định của AI thường vẫn quá khó để nhiều người hiểu. Và việc tương tác với thứ ta không hiểu có thể gây lo lắng, đồng thời khiến ta có cảm giác mình đang mất quyền kiểm soát.

Nhiều người cũng đơn giản là không quen với việc AI hoạt động hiệu quả trong thực tế, vì nó thường diễn ra “hậu trường”. Thay vào đó, họ lại rất chú ý đến những trường hợp AI gặp lỗi. Những thất bại “muối mặt” của AI nhận được lượng đưa tin truyền thông không tương xứng, nhấn mạnh thông điệp rằng chúng ta không thể dựa vào công nghệ. Học máy không phải lúc nào cũng hoàn hảo, một phần vì những con người thiết kế nó cũng không hoàn hảo.)

D. Feelings about AI run deep. In a recent experiment, people from a range of backgrounds were given various sci-fi films about AI to watch and then asked questions about automation in everyday life. It was found that, regardless of whether the film they watched depicted AI in a positive or negative light, simply watching a cinematic vision of our technological future polarised the participants’ attitudes. Optimists became more extreme in their enthusiasm for AI and sceptics became even more guarded.

This suggests people use relevant evidence about AI in a biased manner to support their existing attitudes, a deep-rooted human tendency known as “confirmation bias”. As AI is represented more and more in media and entertainment, it could lead to a society split between those who benefit from AI and those who reject it. More pertinently, refusing to accept the advantages offered by AI could place a large group of people at a serious disadvantage.

(Cảm xúc của con người về AI rất sâu sắc. Trong một thí nghiệm gần đây, những người tham gia với nhiều nền tảng khác nhau được xem một số bộ phim khoa học viễn tưởng về AI, rồi trả lời các câu hỏi về tự động hóa trong đời sống hằng ngày. Kết quả cho thấy, bất kể bộ phim họ xem mô tả AI theo hướng tích cực hay tiêu cực, chỉ riêng việc xem một “viễn cảnh điện ảnh” về tương lai công nghệ cũng đã khiến thái độ của họ bị phân cực. Những người lạc quan trở nên cực đoan hơn trong sự hào hứng với AI, còn những người hoài nghi lại càng dè chừng hơn.

Điều này cho thấy con người thường sử dụng các bằng chứng liên quan đến AI theo cách thiên lệch để củng cố quan điểm sẵn có của mình — một xu hướng ăn sâu trong tâm lý con người được gọi là “thiên kiến xác nhận” (confirmation bias). Khi AI ngày càng xuất hiện nhiều trong truyền thông và giải trí, xã hội có thể bị chia rẽ giữa những người hưởng lợi từ AI và những người khước từ nó. Quan trọng hơn, việc từ chối chấp nhận các lợi ích mà AI mang lại có thể khiến một nhóm lớn người rơi vào thế bất lợi nghiêm trọng.)

E. Fortunately, we already have some ideas about how to improve trust in AI. Simply having previous experience with AI can significantly improve people’s opinions about the technology, as was found in the study mentioned above. Evidence also suggests the more you use other technologies such as the internet, the more you trust them.

Another solution may be to reveal more about the algorithms which AI uses and the purposes they serve. Several high-profile social media companies and online marketplaces already release transparency reports about government requests and surveillance disclosures. A similar practice for AI could help people have a better understanding of the way algorithmic decisions are made.

(May mắn là chúng ta đã có một số ý tưởng để cải thiện niềm tin vào AI. Chỉ cần có trải nghiệm sử dụng AI trước đó cũng có thể cải thiện đáng kể cách nhìn của con người về công nghệ này, như kết quả trong nghiên cứu được nhắc đến ở trên. Bằng chứng cũng cho thấy: bạn càng sử dụng các công nghệ khác như internet, bạn càng tin tưởng chúng hơn.

Một giải pháp khác có thể là minh bạch hơn về các thuật toán mà AI sử dụng và mục đích mà chúng phục vụ. Một số công ty mạng xã hội lớn và các sàn thương mại trực tuyến đã công bố báo cáo minh bạch về các yêu cầu từ chính phủ và việc tiết lộ giám sát. Một cách làm tương tự đối với AI có thể giúp mọi người hiểu rõ hơn cách các quyết định dựa trên thuật toán được tạo ra.)

F. Research suggests that allowing people some control over AI decision-making could also improve trust and enable AI to learn from human experience. For example, one study showed that when people were allowed the freedom to slightly modify an algorithm, they felt more satisfied with its decisions, more likely to believe it was superior and more likely to use it in the future.

We don’t need to understand the intricate inner workings of AI systems, but if people are given a degree of responsibility for how they are implemented, they will be more willing to accept AI into their lives

(Nghiên cứu cho thấy, cho phép con người có một mức độ kiểm soát nhất định đối với quá trình ra quyết định của AI cũng có thể cải thiện niềm tin, đồng thời giúp AI học hỏi từ kinh nghiệm của con người. Chẳng hạn, một nghiên cứu chỉ ra rằng khi người dùng được tự do điều chỉnh nhẹ một thuật toán, họ cảm thấy hài lòng hơn với các quyết định của nó, có xu hướng tin rằng nó vượt trội hơn, và có khả năng tiếp tục sử dụng nó trong tương lai cao hơn.

Chúng ta không nhất thiết phải hiểu tường tận những cơ chế nội tại cực kỳ phức tạp của các hệ thống AI. Nhưng nếu mọi người được trao một mức độ trách nhiệm nhất định trong cách AI được triển khai, họ sẽ sẵn sàng chấp nhận AI bước vào cuộc sống của mình hơn.)

Questions 27-32

Reading Passage 3 has six sections, A-F.

Choose the correct heading for each section from the list of headings below.

Write the correct number, i-viii, in boxes 27-32 on your answer sheet.

List of Headings

-

i An increasing divergence of attitudes towards AI

-

ii Reasons why we have more faith in human judgement than in AI

-

iii The superiority of AI projections over those made by humans

-

iv The process by which AI can help us make good decisions

-

v The advantages of involving users in AI processes

-

vi Widespread distrust of an AI innovation

-

vii Encouraging openness about how AI functions

-

viii A surprisingly successful AI application

27 Section A

28 Section B

29 Section C

30 Section D

31 Section E

32 Section F

Question 33-35

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 33-35 on your answer sheet.

33 What is the writer doing in Section A?

-

providing a solution to a concern

-

justifying an opinion about an issue

-

highlighting the existence of a problem

-

explaining the reasons for a phenomenon

34 According to Section C, why might some people be reluctant to accept AI?

-

They are afraid it will replace humans in decision-making jobs.

-

Its complexity makes them feel that they are at a disadvantage.

-

They would rather wait for the technology to be tested over a period of time.

-

Misunderstandings about how it works make it seem more challenging than it is.

35 What does the writer say about the media in Section C of the text?

-

It leads the public to be mistrustful of AI.

-

It devotes an excessive amount of attention to AI.

-

Its reports of incidents involving AI are often inaccurate.

-

It gives the impression that AI failures are due to designer error.

Questions 36-40

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 3?

In boxes 36-40 on your answer sheet, write

YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

36 Subjective depictions of AI in sci-fi films make people change their opinions about automation.

37 Portrayals of AI in media and entertainment are likely to become more positive.

38 Rejection of the possibilities of AI may have a negative effect on many people’s lives.

39 Familiarity with AI has very little impact on people’s attitudes to the technology.

40 AI applications which users are able to modify are more likely to gain consumer approval.

>> Xem thêm:

-

Roman shipbuilding and navigation [IELTS Reading Cambridge 16 – Test 3]

-

Giải IELTS Reading Cam 16, Test 2: How to make wise decisions

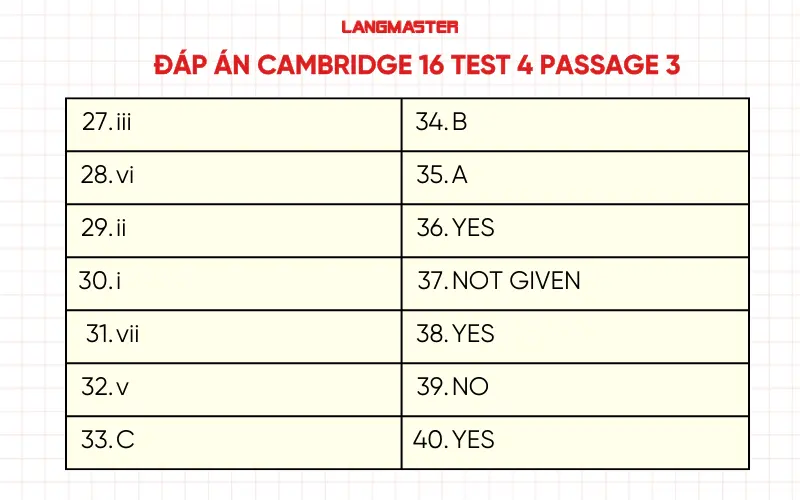

4.2. Đáp án Cambridge 16 test 4 passage 3

27. Đáp án: iii

Vị trí thông tin: Section A – “AI is almost always better at forecasting than we are.”

Giải thích: Đoạn A nhấn mạnh AI đã có thể dự đoán tương lai trong nhiều lĩnh vực và dự báo của AI gần như luôn tốt hơn con người. Vì vậy tiêu đề phù hợp nhất là “AI dự đoán tốt hơn con người”.

28. Đáp án: vi

Vị trí thông tin: Section B – ví dụ Watson for Oncology: PR disaster; bác sĩ nghi ngờ, phớt lờ khuyến nghị AI.

Giải thích: Đoạn B tập trung vào một đổi mới AI cụ thể (Watson) và phản ứng tiêu cực của bác sĩ: nếu AI nói giống họ thì “vô ích”, nếu nói khác họ thì họ cho rằng AI “không competent”, lại không giải thích được nên càng bị nghi ngờ. Đây là bức tranh điển hình của sự mất niềm tin diện rộng vào một ứng dụng AI

29. Đáp án: ii

Vị trí thông tin: Section C – niềm tin vào người khác dựa trên hiểu cách họ nghĩ + trải nghiệm độ tin cậy; AI mới, khó hiểu, gây lo lắng; người ta nhớ lỗi AI hơn thành công.

Giải thích: Đoạn C giải thích vì sao con người tin người hơn tin AI: ta hiểu con người và có trải nghiệm về độ đáng tin; còn AI thì xa lạ, khó hiểu, khiến mất kiểm soát; truyền thông cũng thổi phồng các lỗi AI. Vì vậy heading ii khớp nhất.

30. Đáp án: i

Vị trí thông tin: Section D – xem phim về AI làm thái độ bị “polarised”; optimists cực đoan hơn, sceptics dè chừng hơn.

Giải thích: Đoạn D nói rõ thái độ bị phân cực và ngày càng tách biệt: người lạc quan càng ủng hộ mạnh, người hoài nghi càng cảnh giác. Đây chính là “sự phân hóa gia tăng” về thái độ với AI.

31. Đáp án: vii

Vị trí thông tin: Section E – “reveal more about the algorithms…”, đề xuất “transparency reports… A similar practice for AI…”

Giải thích: Đoạn E đưa giải pháp minh bạch hơn về thuật toán và mục đích của AI, tương tự báo cáo minh bạch của các công ty lớn. Trọng tâm là khuyến khích sự cởi mở/ minh bạch về cách AI hoạt động, nên chọn heading vii.

32. Đáp án: v

Vị trí thông tin: Section F – “allowing people some control… improve trust”; cho phép chỉnh nhẹ thuật toán → hài lòng hơn, tin hơn, dùng nhiều hơn; có “degree of responsibility”.

Giải thích: Đoạn F chứng minh khi người dùng được tham gia/ có quyền kiểm soát một phần, họ sẽ tin AI hơn và sẵn sàng dùng hơn. Đây là lợi ích của việc đưa người dùng vào quá trình AI, nên heading v là đúng.

33. Đáp án: C

Vị trí thông tin: Section A – “we still seem to deeply lack confidence in AI predictions… people don’t like relying on AI…”

Giải thích: Đoạn A chủ yếu nêu ra vấn đề: dù AI dự báo rất tốt, con người vẫn thiếu niềm tin và không thích dựa vào AI. Tác giả chưa đưa giải pháp hay phân tích sâu nguyên nhân ở đoạn này, mà đang “đặt vấn đề” cho toàn bài.

34. Đáp án: B

Vị trí thông tin: Section C – “AI’s decision-making process is usually too difficult for most people to comprehend… can cause anxiety and give us a sense that we’re losing control.”

Giải thích: Đoạn C nói AI khó hiểu, quá trình ra quyết định quá phức tạp, khiến người dùng lo lắng và cảm giác mất kiểm soát. Điều này khớp nhất với ý “độ phức tạp khiến họ cảm thấy bất lợi/ở thế yếu”.

35. Đáp án: A

Vị trí thông tin: Section C – “Embarrassing AI failures receive a disproportionate amount of media attention, emphasising the message that we cannot rely on technology.”

Giải thích: Tác giả cho rằng truyền thông tập trung quá nhiều vào các lỗi “muối mặt” của AI, từ đó nhấn mạnh thông điệp rằng công nghệ không đáng tin, khiến công chúng mất niềm tin vào AI.

36. Đáp án: YES

Vị trí thông tin: Section D – “simply watching… polarised the participants’ attitudes. Optimists became more extreme… sceptics became even more guarded.”

Giải thích: Chỉ cần xem phim sci-fi về AI cũng khiến thái độ của người xem thay đổi theo hướng phân cực mạnh hơn (lạc quan càng lạc quan, hoài nghi càng hoài nghi), nên phát biểu là đúng.

37. Đáp án: NOT GIVEN

Vị trí thông tin: Section D – chỉ nói AI xuất hiện ngày càng nhiều trong truyền thông/giải trí, không nói “tích cực hơn”.

Giải thích: Bài đọc không khẳng định việc AI trong truyền thông sẽ trở nên tích cực hơn; chỉ đề cập hệ quả có thể làm xã hội bị chia rẽ. Vì vậy không đủ thông tin.

38. Đáp án: YES

Vị trí thông tin: Section D – “refusing to accept the advantages offered by AI could place a large group of people at a serious disadvantage.”

Giải thích: Tác giả nói rõ việc từ chối lợi ích của AI có thể khiến nhiều người rơi vào bất lợi nghiêm trọng, tức ảnh hưởng tiêu cực đến cuộc sống của họ.

39. Đáp án: NO

Vị trí thông tin: Section E – “previous experience with AI can significantly improve people’s opinions…”

Giải thích: Câu hỏi nói “familiarity… has very little impact” (tác động rất ít), nhưng bài đọc khẳng định trải nghiệm trước đó có thể cải thiện đáng kể quan điểm về AI. Vậy phát biểu trái với bài.

40. Đáp án: YES

Vị trí thông tin: Section F – “allowed… to slightly modify an algorithm… more satisfied… more likely to use it in the future.”

Giải thích: Khi người dùng được chỉnh sửa nhẹ thuật toán, họ hài lòng hơn và muốn dùng hơn, tức dễ được chấp nhận hơn. Vì vậy phát biểu là đúng.

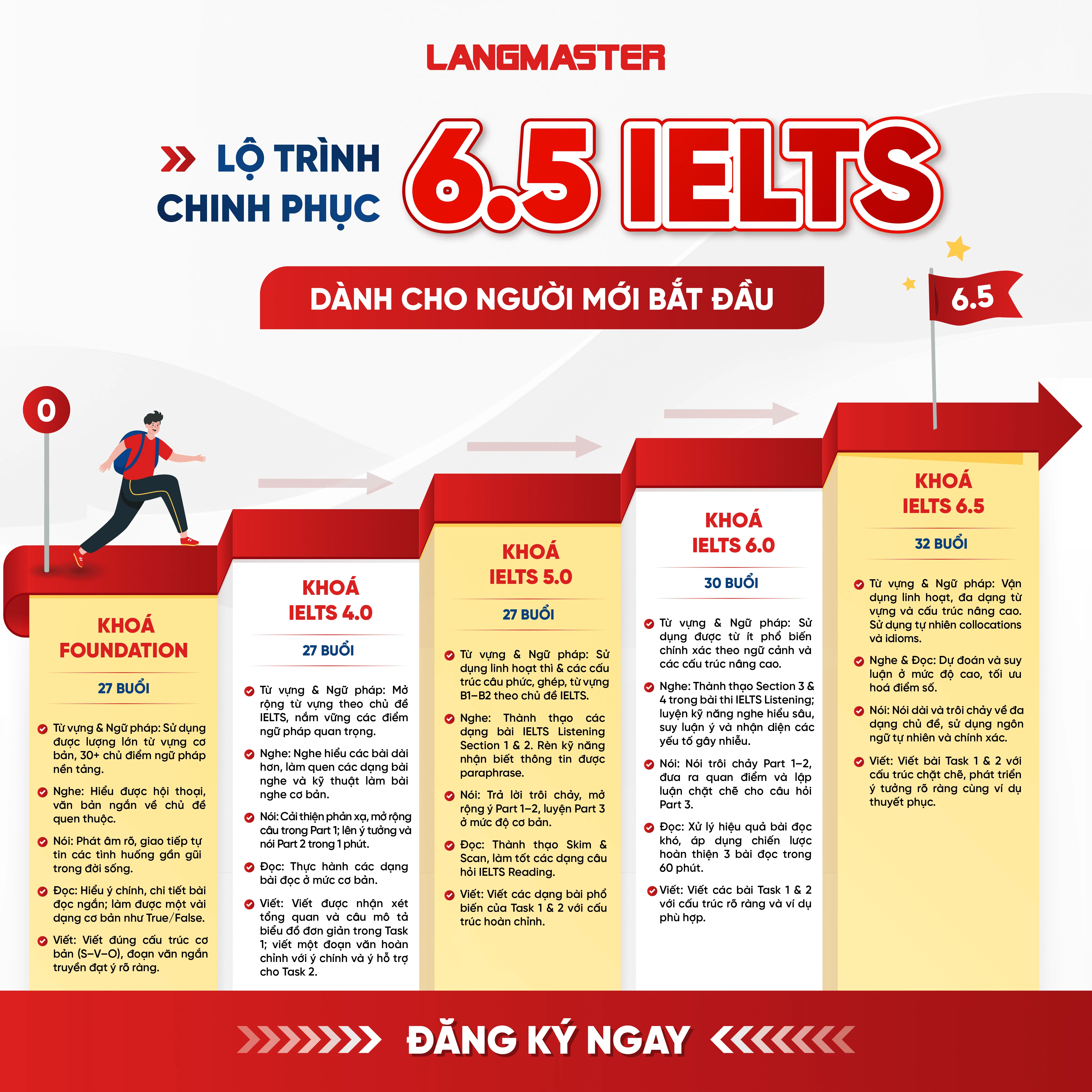

5. Khóa học IELTS online tại Langmaster

Khi luyện IELTS Reading, nhiều người học gặp chung một vấn đề: đọc thì hiểu, nhưng làm bài lại sai hoặc không kịp thời gian. Nguyên nhân không nằm ở việc bạn “chưa học đủ nhiều”, mà ở chỗ chưa được trang bị đúng chiến lược đọc – phân tích – xử lý paraphrase theo chuẩn IELTS. Khi thiếu một hệ thống xử lý bài bản, càng làm nhiều đề càng dễ rơi vào vòng lặp: làm – sai – chữa qua loa – làm tiếp – band vẫn đứng yên.

Thực tế, không ít học viên học IELTS trong thời gian dài nhưng band điểm vẫn “giậm chân tại chỗ”. Họ chăm chỉ làm đề, ghi chép từ vựng, học mẹo rời rạc, nhưng thiếu một lộ trình rõ ràng gắn với mục tiêu band điểm cụ thể.

Với hơn 16 năm kinh nghiệm đào tạo tiếng Anh, Langmaster xây dựng khóa học IELTS online theo tư duy hệ thống, đi từ nền tảng đến nâng cao. Thay vì dạy chung một khung cho tất cả học viên, mỗi lộ trình được thiết kế dựa trên trình độ đầu vào, mục tiêu band điểm và quỹ thời gian thực tế của từng người.

-

Lớp học online sĩ số nhỏ: Mỗi lớp chỉ từ 7-10 học viên, đảm bảo thời lượng tương tác cao. Giáo viên theo sát tiến trình từng người, sửa lỗi chi tiết và điều chỉnh cách học phù hợp với năng lực cá nhân. Đây là điểm khác biệt lớn so với các lớp IELTS online đông người trên thị trường.

-

Lộ trình học cá nhân hóa theo trình độ và mục tiêu band điểm: Trước khi vào học, học viên được đánh giá đầu vào đầy đủ bốn kỹ năng. Qua đó, Langmaster xây dựng lộ trình phù hợp: từ củng cố nền tảng cho người mất gốc, đến luyện kỹ năng làm bài cho mục tiêu IELTS. Từ đó, lớp học không chỉ “học theo giáo trình”, mà tập trung đúng phần cần cải thiện để tránh học lan man và tiết kiệm thời gian.

-

Giáo viên chuẩn quốc tế, chấm chữa kỹ lưỡng: Đội ngũ giáo viên sở hữu chứng chỉ IELTS 7.5+, giàu kinh nghiệm giảng dạy và luyện thi. Bài tập được chấm chữa chi tiết trong 24h, chỉ rõ lỗi sai, nguyên nhân và cách cải thiện cụ thể, không nhận xét chung chung.

-

Luyện đề và thi thử định kỳ theo format thật: Học viên thường xuyên được luyện đề và tham gia các bài thi thử sát đề thi IELTS, giúp học viên làm quen với áp lực thời gian; Nắm rõ chiến lược làm bài và nhận diện điểm mạnh – điểm yếu để điều chỉnh lộ trình kịp thời. Nhờ vậy, người học tránh được cảm giác “ngợp đề” và giảm sai sót do tâm lý khi vào phòng thi.

-

Coaching 1-1 cùng chuyên gia: Phù hợp với học viên cần bứt band trong thời gian ngắn, hoặc gặp khó khăn ở một kỹ năng cụ thể. Giáo viên tập trung xử lý đúng “điểm nghẽn” cá nhân.

-

Học online nhưng không học một mình: Dù học online, học viên vẫn được tương tác trực tiếp với giáo viên, luyện nói thường xuyên, nhận phản hồi liên tục và sử dụng hệ sinh thái học tập hỗ trợ đầy đủ, giúp duy trì động lực và tiến độ học tập.

Trên đây là toàn bộ nội dung dịch đề và giải chi tiết đáp án cho bài IELTS Reading Cambridge 16 test 4, giúp người học nắm rõ ý chính từng đoạn, hiểu cách xác định từ khóa, nhận diện paraphrase và tránh các bẫy thường gặp trong IELTS Reading. Nếu mục tiêu của bạn là học IELTS online một cách bài bản, có lộ trình rõ ràng và được sửa đúng lỗi để tăng band thật, khóa học IELTS online tại Langmaster là lựa chọn phù hợp để rút ngắn thời gian và tối ưu hiệu quả học tập.

Nội Dung Hot

KHÓA TIẾNG ANH GIAO TIẾP 1 KÈM 1

- Học và trao đổi trực tiếp 1 thầy 1 trò.

- Giao tiếp liên tục, sửa lỗi kịp thời, bù đắp lỗ hổng ngay lập tức.

- Lộ trình học được thiết kế riêng cho từng học viên.

- Dựa trên mục tiêu, đặc thù từng ngành việc của học viên.

- Học mọi lúc mọi nơi, thời gian linh hoạt.

KHÓA HỌC IELTS ONLINE

- Sĩ số lớp nhỏ (7-10 học viên), đảm bảo học viên được quan tâm đồng đều, sát sao.

- Giáo viên 7.5+ IELTS, chấm chữa bài trong vòng 24h.

- Lộ trình cá nhân hóa, coaching 1-1 cùng chuyên gia.

- Thi thử chuẩn thi thật, phân tích điểm mạnh - yếu rõ ràng.

- Cam kết đầu ra, học lại miễn phí.

KHÓA TIẾNG ANH TRẺ EM

- Giáo trình Cambridge kết hợp với Sách giáo khoa của Bộ GD&ĐT hiện hành

- 100% giáo viên đạt chứng chỉ quốc tế IELTS 7.0+/TOEIC 900+

- X3 hiệu quả với các Phương pháp giảng dạy hiện đại

- Lộ trình học cá nhân hóa, con được quan tâm sát sao và phát triển toàn diện 4 kỹ năng

Bài viết khác

Các dạng bài phổ biến và tiêu chí chấm điểm IELTS Reading chi tiết nhất: Multiple Choice, Matching Information, Matching Headings,... và hướng dẫn chiến lược làm bài hiệu quả

Những sai lầm khi luyện IELTS Reading bao gồm: dịch từng từ, đọc hết cả bài, không đọc câu hỏi trước, không quản lý thời gian, không nắm vững kỹ năng paraphrase, viết sai chính tả

![Giải đề IELTS Reading: A brief history of humans and food [full answers]](https://langmaster.edu.vn/storage/images/2025/09/20/a-brief-history-of-humans-and-food-ielts-reading-answers.webp)

Giải đề thi IELTS Reading “A brief history of humans and food” kèm full đề thi thật, câu hỏi, đáp án, giải thích chi tiết, và từ vựng cần lưu ý khi làm bài.

Tổng hợp IELTS Reading tips hay nhất giúp bạn đọc nhanh, nắm ý chính và xử lý thông tin chính xác, tự tin đạt điểm cao trong kỳ thi IELTS.

![Giải đề IELTS Reading: The importance of law [Full answers]](https://langmaster.edu.vn/storage/images/2025/09/22/55.webp)

Giải đề IELTS Reading “The importance of law” kèm đáp án chi tiết, từ vựng quan trọng và bí quyết luyện thi hiệu quả để nâng cao band điểm.